Etiology and Pathogenesis of Diverticulosis Coli

B. A. SIKIROV

Abstract

The paper describes a hypothesis as to the etiology and pathogenesis of divet-ticulosis coli. Colonic diverticulosis develops as a result of excessive straining at

defecation due to habitual bowel emptying in a sitting posture, which is typical of Western man. The magnitude of straining during habitual bowel emptying in a sitting posture is at least three-fold more than in a squatting posture and upon urge. The latter defecation posture is typical of latrine pit users in underdeveloped nations. The bowels of Western man are subjected to lifelong excessive pressures which result in protrusions of mucosa through the bowel wall at points of least resistance. This hypothesis is consistent with recent findings of elastosis of the bowel wall muscles, the distribution of diverticula along the colon, as well as with epidemiological data on the emergence of diverticulosis coli as a medical problem and its geographic prevalence.

Introduction

Diverticular disease of the colon is extremely common in developed Western societies, where its prevalence is strongly correlated with advancing age (1). Colonic iverticula represent herniations of the mucosa through the muscle wall at points of weakness; i.e. between the longitudinal taeniae and where the circular muscle is weakened by the segmental blood vessels (2, 3). As herniation implies the existence of a propelling or expulsion force, it has been suggested that colonic diverticula is caused by abnormal pressure in the lumen of the colon (4, 6). Painter suggests that the increased pressure results from a fiber deficient diet which renders the colonic content more viscous and thus harder to propel. In this way, colon segments build up higher pressures which eventually produce diverticula (7). Supporting evidence for the association of fiber and divertitular disease can be found in epidemiologic studies (1). These studies show a prevalence of up to 45% in developed countries as compared with an exceptionally low prevalence among rural Africans. The major difference between these areas of high and low prevalence is reputed

to be that of fiber intake. Recently, serious questions have been raised about whether increased intraluminal pressure is a consistent factor in the cause of diverticular

disease (8, 9, 10). Patients with asymptomatic diverticulosis presented normal colon motility.

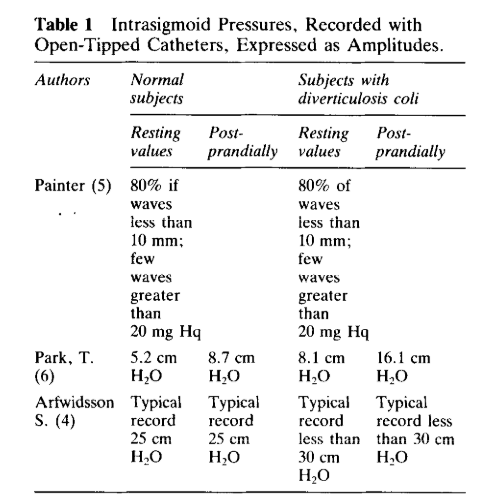

Moreover, changes in motility expressed in terms of a motility index (11) – a product of wave amplitude and the duration of the motor effect which is a widely accepted practice today, may mask the nature of the underlying motor response. This is because waves of greater amplitude may be more damaging to the colon than smaller ones (12). When motor activities are presented as amplitudes, it becomes quite obvious that the colon motilities in diverticulosis at rest and after physiological stimulus such as

eating are not at all or are only slightly higher than those in normal subjects. The absolute dimensions of amplitudes are insignificant (see Table 1) and are unlikely to be destructive to the colon wall.

The results of treatment of diverticular disease with high fiber diets are controversial (13-16). Colonic diverticula have not been found to develop in any species in the wild or on any standard laboratory diet (16). Reports of creating colon diverticulosis in animals by feeding them with a low fiber diet remain disputable (16, 17).

The only realistic source which can lead to the formation of diverticula is the pressure resulting from excessive straining at defecation. The intra-rectal (expulsive) pressures obtained during straining as if attempting to empty the bowels are: 200 mm Hq (18), 100-280 mm Hq (19), and up to 280 cm Hz0 (20). It has recently been found that habitual bowel emptying in a sitting defecation posture requires 5-6 straining episodes, while bowel emptying upon urge in a squatting defecation position

entailed only one and occasionally two straining episodes (21). The latter defecation pattern is typical in the underdeveloped nations where bowel emptying is still done in a pit latrine (22). Thus the colon of Western man is subjected to at least three times more expulsive pressure than the colon of people practicing bowel emptying on urge and in a squatting posture. The reduced amount of straining during bowel emptying in a squatting posture and in response to urge is a consequence of the straightening out of the rectoanal angle and of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, respectively (21, 23, 24). A high fiber diet accelerates the achievement of rectal volumes, evoking the feeling of urgency and the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, thus reducing the magnitude of straining (21). However, the principal factor in the reduction of the magnitude of

straining, expressed as a reduced number of straining episodes, appears to be a squatting defecation posture and the accdmpanying straightening out of the rectoanal angle. The increased thickening of both the circular muscle layer and the longitudinal taeniae coli is the most striking and consistent feature in divertitular disease of the sigmoid colon (2.5, 26). Neither hypertrophy nor hyperplasia of the muscle cells has ever been convincingly demonstrated. Recently, examination of surgical specimens of the sigmoid colon affected by diverticulosis under light and electron microscopy revealed that a thickening of the longitudinal taeniae is associated with an increased

elastin content (26). The initiating factor in the etiology of elastosis of longitudinal taeniae can be found in the work of Y. M. Leung et al. In an investigation of the relationship between mechanical forces and the synthesis of connective tissue components by smooth muscle cells, the authors found that cyclic stretching of

smooth muscle resulted in a two- to fourfold increase in the rate of collagen, hyaluronate and chondroitin 6-sulfate svnthesis over those in agitated or stationary preparation (27). Cyclic stretching of the bowel wall muscle occurs repeatedly during defecation as a result of the expulsive efforts. The bowel of Western man is

subjected to excessive stretching and pressure as a result of the extra expulsive effort. These are cumulative throughout life and eventually result in elastosis of the bowel muscle and/or herniations of mucosa through the bowel wall at points of least resistance. With advancing elastosis and shortening of the longitudinal taeniae, the lumen

of the sigmoid colon is narrowed (25, 26). As a result, the bowel wall, in accordance with Laplace’s law, is subjected to increased pressure (28) during every expulsive effort, thus increasing the chances of herniations at this stage. Incidence of diverticula in different parts of the colon (29) can be readily explained on the basis of their relation to the rectum, the epicenter of expulsive pressure.

Segments of the colon nearest this epicenter should have a greater possibility of being affected by diverticulosis. The rectum lies at the epicenter. However, diverticula are never seen in this portion of the bowel (30). This can be explained by the absence of areas of relative weakness in the rectal wall. While the longitudinal taeniae run along the entire length of the colon as three discrete taeniae at the recta-sigmoid junction,

they fuse completely, encircling the rectal wall (31). Thus, like all other parts of the digestive tract, the rectum has an inner circular coat, while unlike other parts of the colon, it has a uniform coat of longitudinal musculature. The circular fibers of the rectal wall form a thick layer (31). Thus, diverticular formation in the rectum is

prevented by a heavy double muscular coat. With the exception of the rectum, all other parts of the colon have areas of diminished resistance at the bowel wall (2, 3). The sigmoid is the segment of colon nearest to the epicenter of the above-mentioned expulsive pressures, which are therefore most commonly affected by diverticulosis.

Other parts of the colon are located further from the rectum (epicenter of expulsive pressure) and are separated from it by the sigmoid colon. thus explaining the less frequent incidence of diverticulosis in these segments. Nevertheless, when proximal segments of the colon are affected, they are invariably in conjunction with

the involvement of the sigmoid. The hypothesis presented here as to the cause of diverticulosis coli is consistent with epidemiological data about its emergence as a medical problem and its geographic distribution. The steep increase in diverticular disease in England from 1910 onward has been attributed by British physicians to the introduction, around 1880, of roller milled wheat flour, resulting in a lower intake of crude cereal grains (1). However, at the same time another factor entered the life of

Western man. In the early 19th century. as a result of the successful development of sewage systems.

toilet seats began to be installed in increasing numbers (32). As the development of diverticulosis coli reflects the long term use of a sitting posture while defecating, the dramatic rise in the incidence of diverticulosis in Western

countries at the turn’ of the century can be explained by the introduction of toilet seats into the life of the economically developed countries from the early 19th century onwards. The near absence of diverticulosis coli in rural Africans was attributed by Burkitt and Painter to a high fiber diet (1). This overlooks the fact that rural

Africans continue to utilize the pit latrine for defecation. The incidence of diverticulosis coli in American blacks. descendants of African immigrants, was found to be the same as in Western man in general and was attributed to a typical low fiber diet (1). Again it seems that the authors were unaware of the additional changes in the habits of American blacks regarding defecation in the usual Western sitting posture.

Conclusions

Controlled trial with a group of patients suffering from symptomatic diverticulosis coli and ready to adopt an exclusively squatting position for defecation and on urge may confirm the hypothesis presented.